Iron Fist's Impossible Architecture is Inspired by an 18th-Century Architect

Danny Rand meet Giovanni Battista Piranesi

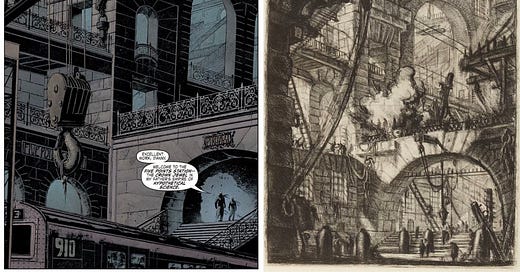

In The Immortal Iron Fist #4, written by Matt Fraction and Ed Brubaker, modern-day Iron Fist Danny Rand meets his predecessor, Orson Randall — a twentieth-century adventurer in the mold of Doc Savage. Randall isn’t just another adopted son of K’un-L’un; he’s also the son of a mad scientist who we’re told little about beyond two crucial details:

1. He wears a top hat.

2. He built a secret “hypothetical" train system beneath the Manhattan subway.

It’s a great issue in a great run. But as a recovering architect, I was even more thrilled to see the design of the “hypothetical” subway station shown. Enormous stone vaults. Stairs and bridges that lead nowhere. Ominous chains and pulleys...

It's a direct homage to the works of eighteenth-century Italian architect Giovanni Battista Piranesi.

More Historical Than History

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778) was an architect who wasn't known for his buildings, which were few, but for his incredibly detailed etchings of Roman ruins. His work fuses a deep love for antiquity with a wild imagination. At a time when European scholars were debating the origins of Classical architecture, Piranesi became widely successful by producing grand visions of a past that never quite existed.

Even his contemporary views of Rome didn’t show ruins as they were, but as we wish they were. He exaggerated scale, deepened shadows, and distorted perspectives to make ruins more imposing and dramatic. It's said that the German poet and philosopher Goethe, who came to know Rome through Piranesi's widely distributed prints, was disappointed when he eventually came to visit the Eternal City.

His etchines are more Rome than Rome.

Piranesi's embellishments and reinventions make viewers feel the heroic grandeur and tragic fall of an empire. He gives Ancient Rome a mythical quality that would inspire generations of painters, writers, and architects.

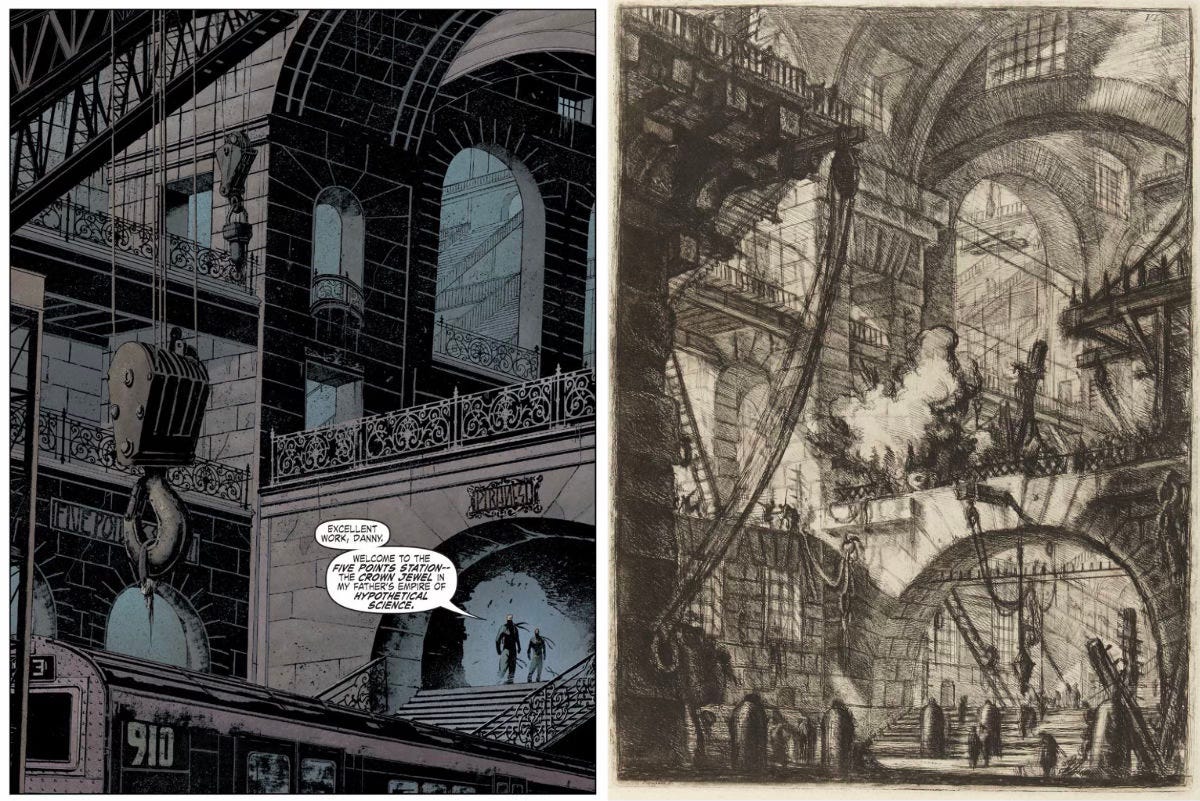

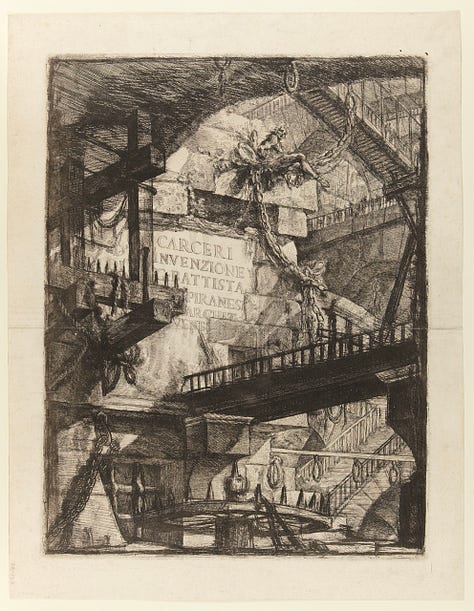

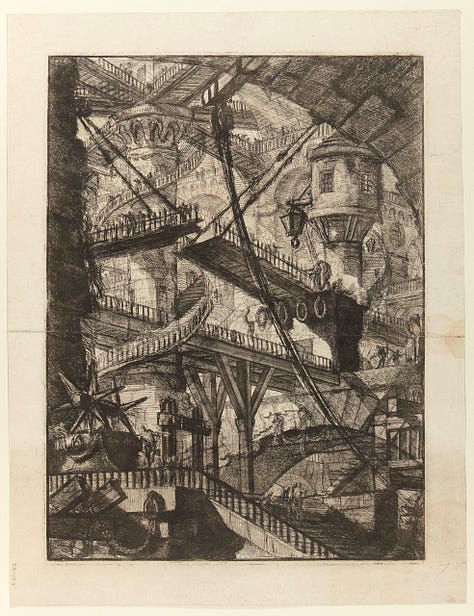

But his most enduring series, Carceri d’Invenzione (Prisons of the Imagination), goes even further.

The Beauty and Terror of Architecture

The Carceri depict vast, impossible prisons whose colossal spaces and towering arches dwarf tiny, faceless figures who seem trapped within. There’s no explanation. No story or logic. Just a lingering feeling of anxiety.

These spaces are both awesome and oppressive. First published in 1740, this work is an early artistic expression of the sublime — the idea that grand beauty can inspire not only awe but terror as well. In the following century, painters like Caspar David Friedrich and J.M.W. Turner captured this concept in nature’s raw power.

Piranesi found it in architecture.

Piranesi's subterranean sublime isn't just terrifying because of its decay or ruin. It's terrifying because of the implicit intent behind it. Someone designed these spaces. Someone put their ingenuity and skill to work to create something complex and inescapable and so profoundly...cruel.

Some people have speculated that the Carceri were inspired by fever dreams, others that they were simply a talented architect and draughtsman exploring the relationship between form, space, and geometry. Whatever the reason, Piranesi’s work left a permanent mark on how we imagine impossible spaces.

Designing a Sublime Universe

Just as “Kafkaesque” describes surreal, nightmarish bureaucracies, “Piranesian” has become shorthand for vast, labyrinthine spaces that defy reason. Architecture stretched beyond human scale and understanding. Endless corridors, staircases twisting in on themselves. The kind of place where escape feels impossible.

Piranesi supposedly told an early biographer, "I believe that if I were commissioned to design a new universe, I would be mad enough to undertake it.”

Such a universe might look a lot like what we see in Iron Fist. Danny Rand exists in a beautiful yet terrible world of hidden cities, pocket dimensions, mystical doorways, and, apparently, hypothetical infrastructure systems concealed in the bowels of the earth. It makes perfect sense to see impossible architecture in this world.

Piranesi’s prisons weren’t meant for humans. They were meant for superheroes.