How Eliot R. Brown designed Gotham City

Looking back at the creation of Gotham City 25 years after No Man's Land. An interview from my archives, but still full of insight from one of comics' great creators.

Growing up, all my favorite books had maps in the front. They made stories feel so much more real and immersive. What secrets, dangers, and adventures were waiting for the characters on those maps? I couldn’t wait to find out. And what about those places the story never took us? Those were the most important. Anything could happen there.

I could decide what happened there.

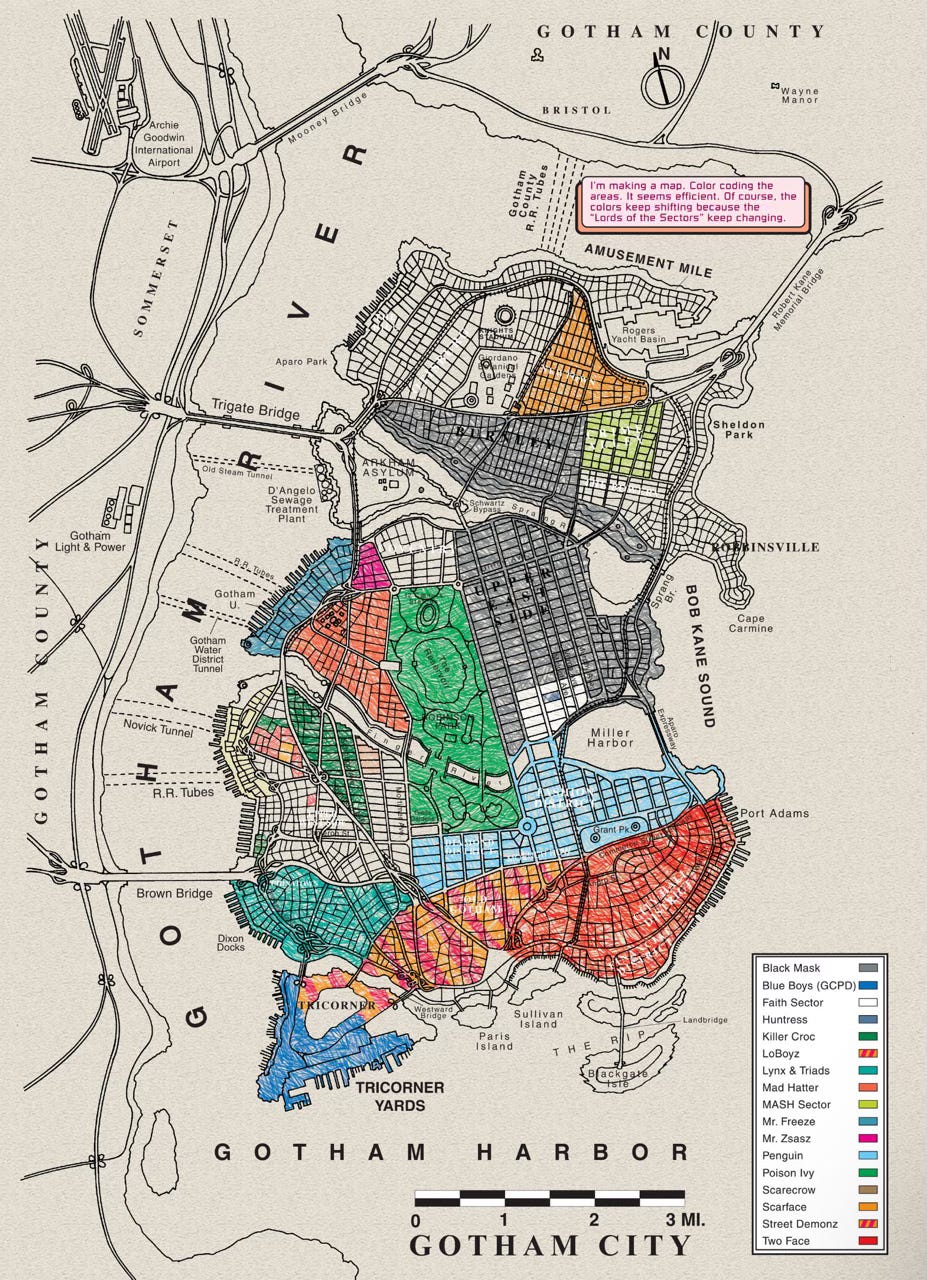

So in 1998, when I turned a page in Batman: No Man’s Land #1 and saw a map of Gotham City, I was thrilled. Here was the realistically detailed map of Gotham that I never knew I always wanted. This new view of Gotham, with its neighborhoods marked as villainous fiefdoms, set up years of storytelling.

Years of storytelling just from a map.

But where did that map come from? When were Gotham City limits first defined?

In the early days of comics, cities weren’t much more than rooftop set pieces and vaguely defined skylines. For years, Batman was basically fighting crime in a generic version of New York. This architectural ambiguity was intentional. As Batman co-creator Bill Finger has said, “We didn’t call it New York because we wanted anybody in any city to identify with it.”1 In fact, they didn’t call it anything for the first year of Batman’s war on crime. Gotham City wasn’t mentioned by name until Batman #4.

“We didn’t call it New York because we wanted anybody

in any city to identify with it.”

Bill Finger, Co-creator of Batman

Since then, Gotham has grown from a generic non-place to the most complex and fully realized city in comics. That reality is due, in large part, to something that almost no other comic book city has: a map.

The Map-maker of Gotham

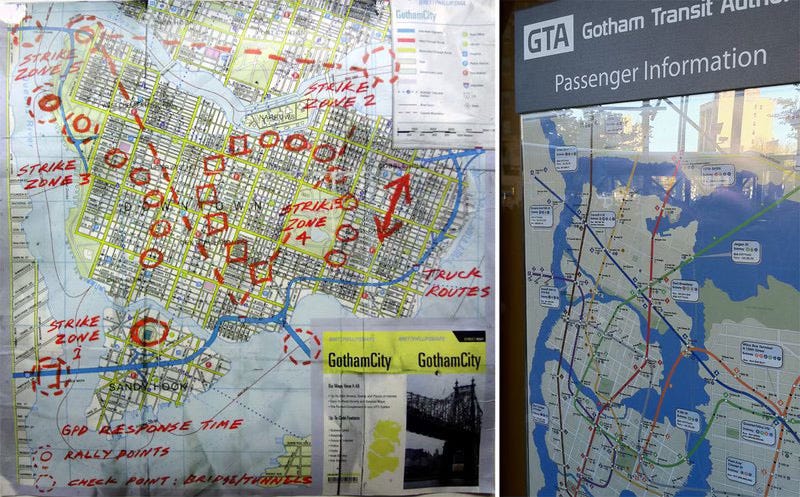

Gotham City limits were established in preparation for the “No Man’s Land Story” story arc, which was set after a cataclysmic earthquake. But before DC Comics could destroy Gotham City, they needed a Gotham City to destroy. No Man’s Land was a major crossover event, and DC wanted a map of the city as part of an in-house “bible” to help writers and artists coordinate their stories across titles.

Enter artist and illustrator Eliot R. Brown, the cartographer of Gotham.

Brown had previously worked at Marvel as a sort of “in-house architect,” as he told me via email, dreaming up and drawing up specifications for Punisher’s weapons, Iron Man’s armor, and the occasional superhero headquarters (more on that in a future post). But I was curious, did Brown have any experience designing cities?

Brown: “I have always been interested in maps and map-making. When my wife took cartography in college I knew pretty much everything she did. I wanted to be an architect, but chose the wrong decade to try it. And I was a lack-luster student. I had been spoiled by hard-core architectural teachings at the High School of Art & Design. But then to go in for two years of "pre-reqs" [before I could study architecture in college] just was too much.

“But I was the closest thing Marvel had to an in-house architect and architectural renderer (and weapons designer and aerospace engineer). When the Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe (OHOTMU) started up, I was positioned to be the "tech page" guy and there were a couple of maps done for that. The Gotham Map was an offshoot of that project. The Editor In Chief of DC [then Mike Carlin] had been the Assistant Editor to the Marvel Editor who dreamed up OHOTMU [Mark Gruenwald].”2

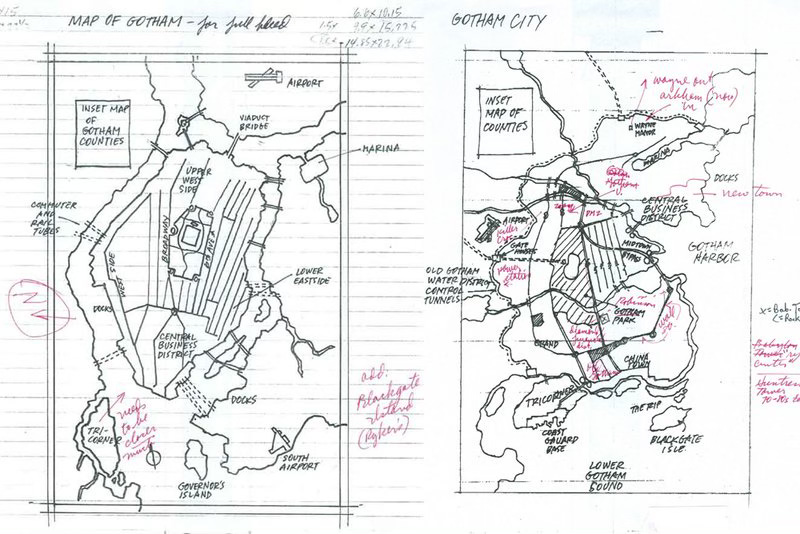

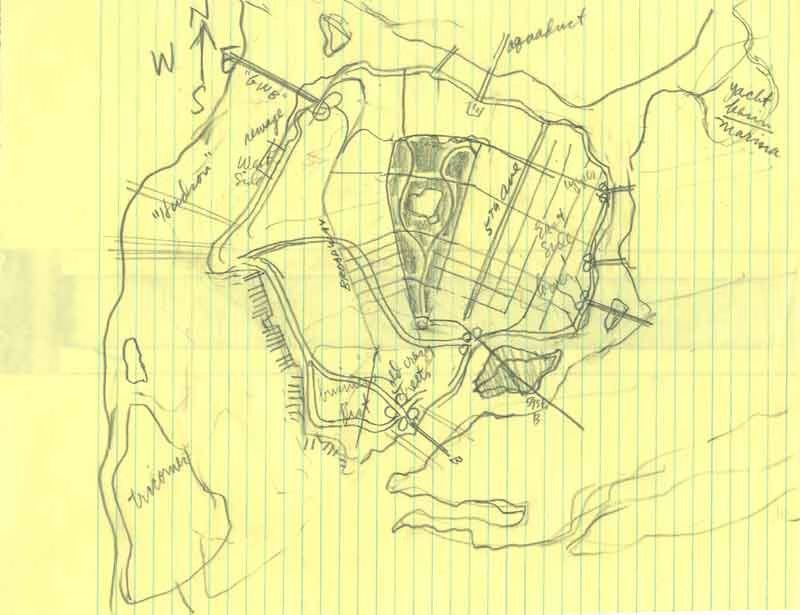

The first step for Brown was to meet with the writers and artists who shared some early story notes along with their wish lists for Gotham locales. As he recalls:

“The DC Comics editors made it clear that Gotham City was an idealized version of Manhattan. Like most comic book constructs, it had to do a lot of things. It needed sophistication and a seamy side. A business district and fine residences. Entertainment, meat packing, garment district, docks and their dockside business. In short all of Manhattan and Brooklyn stuffed into a … well, a nice page layout.”3

Oh, is that all?

With research in hand and a mandate to make Gotham an island, Brown began, like Bill Finger, with the idea of a fictionalized Manhattan. Brown grew up in New York and knew it well. He used that knowledge to plan its fictional counterpart, sprinkling in familiar neighborhoods, parks, civic buildings, monuments, landmarks, and transit infrastructure.

Brown gave the city its rough shape over a week. After some testy exchanges with editors and a few back-and-forth faxes, he finalized its boundaries and infrastructure less than two months later. Brown’s final hand-annotated map of Gotham City included numerous bridges and tunnels ready to be dynamited by the U.S. government, as well as a few forgotten steam tunnels that might be useful to a crimefighter and his allies.

Eliot R. Brown didn’t just design Gotham City, he seeded stories and designed an implicit history that writers are still exploring more than 25 years later.

“[DC Comics wanted] all of Manhattan and Brooklyn

stuffed into…well, a nice page layout.”

Eliot R. Brown

When “No Man’s Land” ended in 1999 and Gotham returned to the status quo—rebuilt with money from Bruce Wayne and Lex Luthor—the map of the city stayed canon. It has remained more or less intact for 25 years.

No small feat in an industry known for relaunches, reboots, and reimaginings — not to mention retroactive continuities.

The map has even been featured in films and videogames—most notably, Christopher Nolan’s films. Brown was unaware of this new life for his map but told me he was “delighted that it has helped further the ‘reality’ of Batman.”

The Limitations of Cartography

While a map may seem unnecessary for a fictional city, it really does give Gotham a unique and defined identity. So why don’t more comics map their cities? Why isn’t there a definitive Metropolis or a definitive Star City?

I asked Brown that question:

“The truth was the Gotham Map came at a time when DC was trying for a ‘Ka-Boom’ every year. Carlin had killed Superman. Which sold a lot of books. Then it was deemed a good idea to figure out something big to do every year. The map of Gotham came along when the ‘Cataclysm’ struck. An earthquake devastated the area of and around Gotham City…[and] the President cut off the city from the mainland. Yes! You've heard it before... Escape From Gotham City!

The real reason editors and comic people don't do for real maps. Sheer, utter, and childishly self-indulgent laziness on the writers' part. If a writer wants Batman to face Croc on a glacier-bound treehouse for mutants — then that's what he writes and what gets drawn. If, the next month, Batman is now chasing Harley Quinn at a 24-Hour Endurance Sports Car Race Track — poof, there it is. All right in Gotham City. Put in a better way, it is about allowing the writers to have their freedom.”

Strong words here (and in excerpts I’m leaving unpublished)! Brown is clearly passionate about his work. But, to extrapolate a little on what he says, it’s interesting to think of comics that aren’t just a union of writing and art, but writing and art and cartography or urban design.

That said, I think the desire for freedom is surely one deterrent to mapping comic cities, as is the editorial and financial investment needed to create a city. But there’s another challenge here.

Designing a city is hard.

Centuries of architects and urbanists haven’t really cracked it in any meaningful way. Most planned cities—places like Brasilia, Canberra, and Celebration—oscillate between feeling inhuman and feeling like a stage set. The maps are too rigorous. Too logical. Designed from the top down by urban planners imposing grids and patterns and their own will onto wild landscapes.

Most cities grow from the bottom up, shaped by the people who live there — not analysts studying maps. Cities evolve in response to culture, resources, regulations, traditions, technologies, ideas, a little bit of magic, and so much more. Maps don’t make cities. People do. And that makes Gotham all the more impressive to me.

Eliot R. Brown’s map of Gotham City is extraordinarily executed. A pastiche of New York and Chicago and who-knows-where that feels entirely original and realistic because, in part, it was inspired by people — vigilante crimefighters, specifically. But also artists and writers and editors who all had a unique vision for their stories, building on 50 years of history.

It feels like a place that grew organically because…it kind of did.

Once-and-future Batman writer

has mined Gotham’s map and urbanism more than most, making extensive use of the city’s architecture and urban design. For Snyder, Gotham is a reflection of Batman’s identity. He uses the city to tell complex, layered stories rich with metaphor, history, symbolism, and exploding buildings. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that Snyder, like Brown, grew up in New York.Snyder’s 2011 Batman run started with an enormous urban renewal project. That same year, he worked with

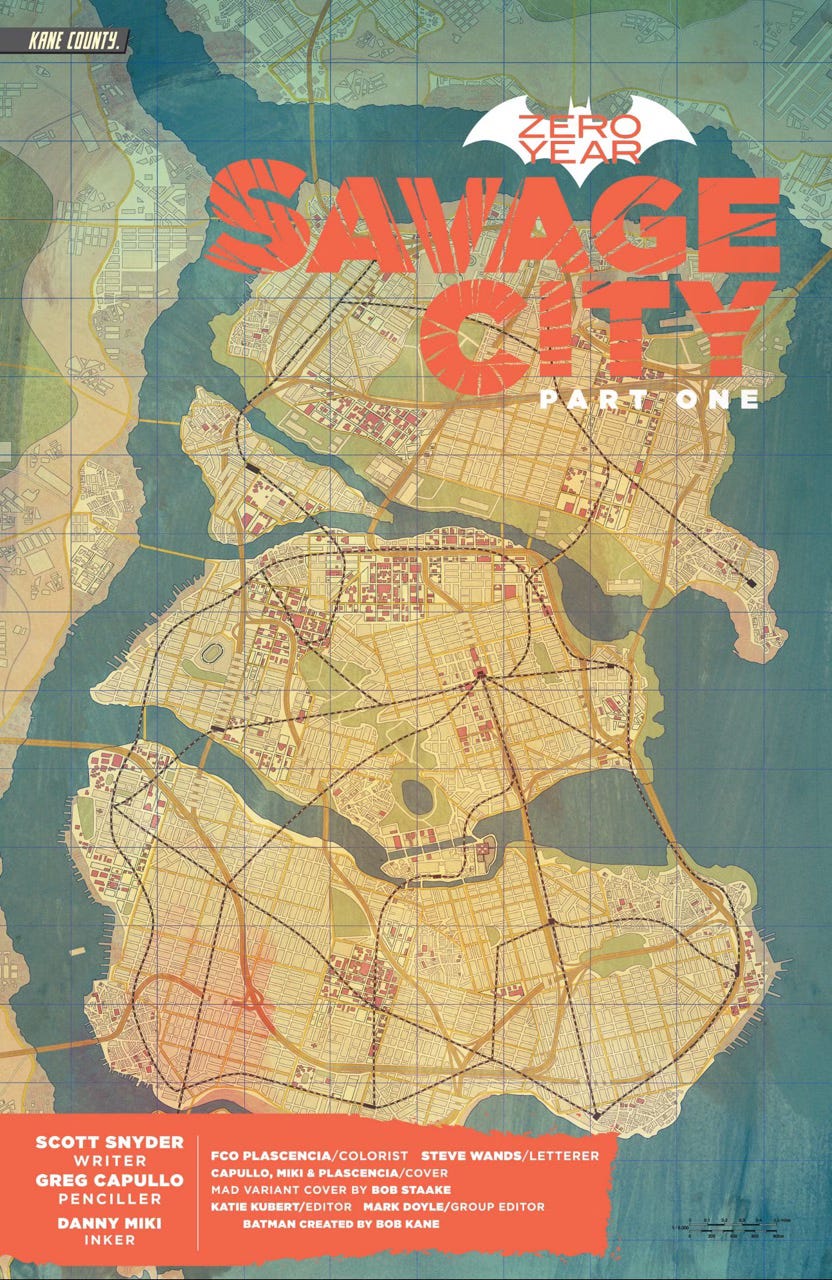

and Ryan Parrot to craft the story Gates of Gotham, which tells the tragic tale of the bridges you see on Brown’s map. And when it came time to refresh Batman’s origin in a No-Man’s-Land-style story, he featured an updated version of Brown’s map in issue 30.Still makes for a nice page layout.

Eliot R. Brown no longer works in comics and hasn’t been keeping up with the stories (though he was glad to know his work lives on). Sadly, his career ended during a particularly low point in comics history.

“My time at the official ‘end’ to my career was fraught with question and unhappiness. Within a few years of my dismissal (1986) I saw comics sink in quality and I gave up trying to keep up. Not long after, the company was bought by corporate raiders who got in a shareholder battle and caused the company to go bankrupt… . I also never had a real affinity with super-heroes and attendant super powers. All my ‘books’ for example, were about regular people, Nick Fury, Tony Stark and Frank Castle doing unusual, often technological, things. For that matter, even Batman is ‘just’ a man.”

Brown was drawn to realistic characters and his legacy lives on in the reality he brought to comics. In the diagrams and cut-aways readers spent hours pouring over and artists recreating. In Punisher’s Armory, Tony Stark’s armors, and, most notably for me, Gotham City.

Since No Man’s Land, writers have populated Gotham with new characters and places, making it a little more real with every story. Freedom is important, but restrictions can create the best art. With every name they add to the map—The Narrows, The Hill, Burnside, Gotham Academy—Brown’s legacy gets stronger and Gotham becomes more real. Giving these places a name is giving them an existence. And putting them on the map anchors them to the reality of the world.

But as in the real world, it’s not the names that truly matter. It’s the people. The characters, culture, and history.

It’s the stories.

Stories breathe life into places that were once just lines on paper.

Thanks for reading! Please consider sharing this post if you like it! I can’t be the only one geeking out about made-up maps and apocryphal architecture.

And if anyone from DC Comics reads this and finds themself looking for a Eisner-nominated writer with a background in architecture history and a penchant for place-based storytelling, let’s talk!

Recommended Reading

No Man’s Land — Following an earthquake, Gotham becomes a war zone. It’s up to Batman and his allies to restore law and order in one of the Dark Knight's greatest epics.

Batman: Court of Owls — Batman discovers a secret society controlling Gotham City for centuries in writer Scott Snyder and artist Greg Capullo's famed storyline.

Batman: Zero Year — Witness the beginning of Gotham’s heroes, as the Riddler cripples Gotham City in the early days of Batman's career.

Gates of Gotham — When a mystery as old as Gotham City itself surfaces, Batman assembles a team of his greatest detectives to investigate this startling new enigma that explores different eras in Gotham's sordid history!

Batman: Destroyer — Batman's investigation into a series of bombings uncovers documents detailing the role of his ancestor Solomon Wayne in the creation of modern Gotham City!

Red Hood: The Hill — Welcome to the Hill-formerly one of Gotham’s most dangerous suburbs-a place that required its residents to band together to keep themselves safe when the police, and sometimes even Batman, wouldn’t.

Bill Finger, quoted in The Steranko History of Comics, Vol.1 (Supergraphics, 1970)

The interview excerpted for this article was originally conducted by Jimmy Stamp in 2014 for an article in Smithsonian Magazine. It has been condensed and lightly edited.

This quote excerpted from Brown’s personal website.

This is a rad article! I sent to my friend who is a geographer!